Hundreds gathered along the Mississippi this past weekend for the Owamni Falling Water Festival – a celebration of Indigenous Minnesota cultures.

And President Biden proclaimed October 11 Indigenous Peoples Day.

Here’s Chioma Uwagwu with these stories:

This past Saturday, indigenous artists and educators gathered on either side of the Stone Arch Bridge in Minneapolis for the Owamni Festival. Owamni means ‘falling water’ in the Dakota language.

18-year-old Nathan attended the festival. He explains that “in native culture, we believe that everything has a spirit and, you know, we have to respect everything the same as we respect others. And so we give everything that same respect and you know, humans cannot live without water.”

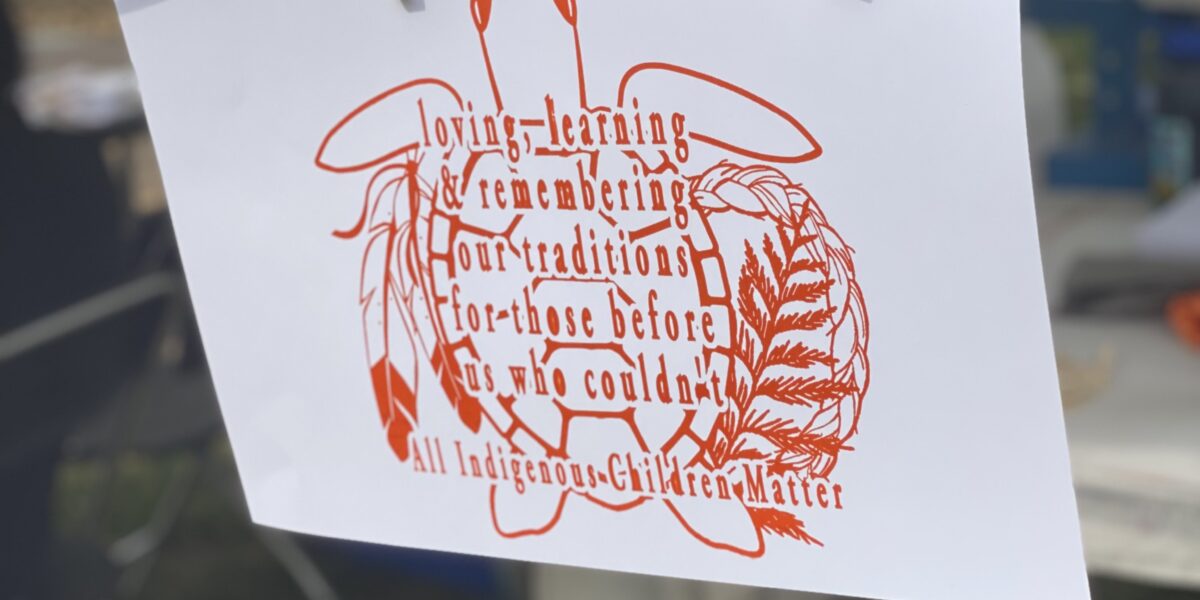

Indigenous artists offered their jewelry, graphic art and blankets for sale. Food trucks sold local indigenous foods. In addition to putting money directly in the hands of native vendors, the festival offered up a range of entertainment, with revolving acts by singers, drummers and comedians.

At one of the educational booths was Amber Annis, a citizen of the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe and the program and outreach manager in Native American Initiatives at the Minnesota Historical Society. Annis says festivals like these are important not just to indigenous people, but people of all walks of life.

The festival came just a day after President Biden made the first ever presidential proclamation of Indigenous Peoples’ Day. Annis says it’s about time.

“I think that we have to reckon with the really hard part of colonialism, extractive colonialism, settler colonialism – these things that really have shaped all of our communities today, to a degree,” Annis said. “I think the maturity to be able to say that, at this point in 2021, we are at a time where we no longer should be celebrating and highlighting these figures that were crucial in the genocide of native people, in the theft of land, in the murder of indigenous people. So for me, I think that it’s just really important because we all should be there, collectively responsible, and understand that highlighting Indigenous People’s Day is not just for native peoples, it’s for everybody.”

Indigenous Peoples Day was observed on Monday, the same day as the federal holiday Columbus Day. Columbus Day first became a national holiday in 1937 as a way to honor the achievements of Italian Americans. But Native Americans have protested the holiday for decades, because it erases thousands of years of Native history, and because Columbus tortured and enslaved Indigenous people.

Many would like to see Columbus Day eliminated altogether and replaced with Indigenous Peoples’ Day. That would take an act of Congress.

Tom LaBlanc, a member of the Sisseton Wahpeton Dakota Tribe, says he thinks the U.S. government has resisted recognizing Indigenous history and culture over the years because it contradicts western values.

“And as long as they continue to allow Columbus and that kind of mentality to survive, we’ll never face the truth,” said LaBlanc. “And so, we need people to open up their eyes and ears and, and heart and begin to make a better spirit and a better human being so that we have something for our kids and grandkids. I don’t want to have to pass on the legacy of what we have today. So they can continue on with Columbus and we’ll tear down the statues, or ignore it, and have our own celebrations because we represent life, not death.”

While Minnesota celebrates Indigenous People’s Day, it is not a legal holiday. Many cities across the country still recognize the second Monday in October as Columbus Day.

Chioma Uwagwu reporting for Minnesota Native News.

Booster Shots, Vaccination Rates, and Looking Ahead to Vaccines for Young Ones

Booster Shots, Vaccination Rates, and Looking Ahead to Vaccines for Young Ones